Until now, the menstrual cycle has played little role in training planning. Yet it could be put to good use to improve performance.

Men have a daily best form, women a monthly best form. This is because the levels of the male sex hormone testosterone are significantly higher early in the morning than during the day, but they fluctuate only slightly over the course of a month.

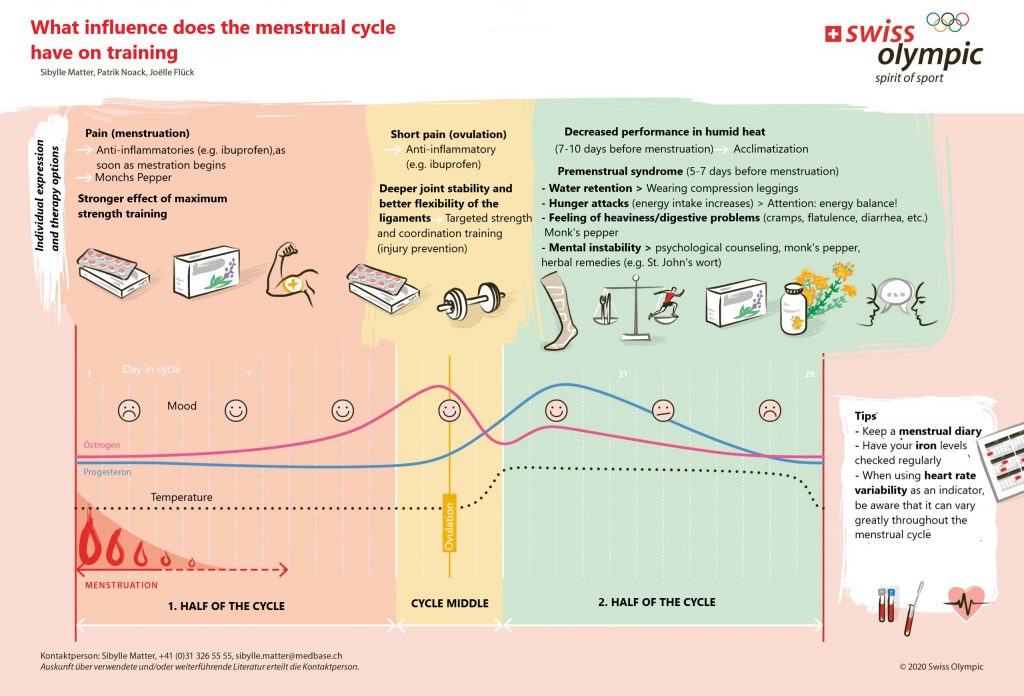

In women, on the other hand, the sex hormones rise and fall in the cycle of about 28 days. Estrogen and progesterone (corpus luteum hormone) in particular play a role. The natural fluctuations of these hormones can influence training both positively and negatively.

In the first half of the cycle, until ovulation, cycle-controlled training is primarily about increasing strength and endurance. Training intensity then increases until shortly after ovulation. In the second half of the cycle, the focus is on maintaining strength and endurance, and training intensity decreases again.

This is how the cycle and training influence each other:

Phase 1: Menstruation (follicular phase).

“Women should take it easy during menstruation,” used to be the advice. However, women who are active in sports and have no pain during menstruation often perform better. However, about one in three female athletes actually experiences a reduction in performance in connection with the menstrual cycle.

Maximum strength training has the strongest effect at the onset of menstruation. This is when the anabolic effect of estrogen can be best exploited. The female sex hormone estrogen supports muscle building, increases bone density, elevates mood and promotes regeneration. At the beginning of the follicular phase, the concentration of estrogen is still low, but then gradually increases during the course and reaches its peak during the cycle shortly before ovulation.

High-intensity strength training in the first phase of the cycle can also raise the level of the (typically male) sex hormone testosterone in women, which additionally promotes muscle building.

Training does not usually help against menstrual cramps. More effective are anti-inflammatory painkillers such as ibuprofen (right at the beginning and not only when the pain is fully developed). If the pain is regular, a specialist examination is advisable to rule out other causes (for example, endometriosis).

If menstruation does not occur, female athletes should consult their doctor. This may be a sign that the stress level is too high and that rest and/or nutrition are being neglected. This can have devastating consequences for health, for example lower bone density for years to come.

Phase 2: Ovulation

Around the time of ovulation, the ligaments are more flexible and give less support to the joints. Therefore, the risk of injury is higher during the mid-cycle days. To prevent this, targeted strength and coordination training is useful. The estrogen level now decreases, while the corpus luteum hormone begins to increase.

Phase 3: Formation of the corpus luteum (luteal phase).

The level of the corpus luteum hormone continues to rise after ovulation. This is accompanied by a slight increase in body temperature. This can somewhat reduce the performance of the cardiovascular system, as several studies have shown.

If the egg is not fertilized, progesterone decreases again. This causes the effects of estrogen to be more predominant, which is why the body stores more water in the week before menses and body weight increases. Hunger also increases and hot and humid weather is less tolerable. Combined with a feeling of sluggishness as well as mood swings and increased perception of problems, this is called “premenstrual syndrome” (PMS). Falling progesterone levels at the end of the luteal phase are often associated with PMS. Towards menstruation, both estrogen and progesterone levels drop to the lowest levels during the cycle.

Compression leggings for the legs, supplements such as monk’s pepper, St. John’s wort, or psychological training can help. Sometimes synthetic hormones (birth control pills, hormone pills, hormone patches, vaginal rings) are also useful. However, it is important to assess and discuss the risks individually with a sports doctor or gynecologist beforehand. In addition, hormonal contraception should, if possible, be tried during a less important sporting phase.

However, cycle-controlled training only works if the athlete has her natural cycle. This is because the “birth control pill” or other hormonal preparations paralyze one’s cycle and, depending on the body, may not have the same effect.

Here is a good graphic that shows how the hormones change during the cycle and what the body temperature does:

Source: Swiss Olympic

Competition and menstruation

Postponing menstruation before an important competition with the help of artificial hormones only makes sense for top athletes if they suffer from severe menstrual cramps and have exhausted all other options.

The tolerance of such hormones should be tested at least one year before the competition. Which is most suitable (e.g. pill with/without progestogens or hormonal IUD) should be discussed in advance with the doctor, as should possible risks such as thrombosis.

Athletes who already take the pill regularly can usually delay menstruation by two to three months by skipping the hormone-free window, which usually lasts seven days. However, this should also be discussed with a doctor beforehand.

Tips

- Cycle-related fluctuations in performance are acceptable. They rarely require treatment.

- Keep a menstrual diary or use apps and wearables such as “FitrWoman” to record your athletic performance and other factors. This will help you find out if and how hormonal fluctuations affect your performance.

- During menstruation, all types of sports are possible, provided that the bleeding can be controlled well (for example, with a tampon or menstrual cap).

- Those who are prone to anemia should have their blood levels checked regularly, especially if they are on a vegetarian diet.

- The cycle due to the “pill” or other hormone treatments can influence both the negative and the positive effects.

- The risk of venous thrombosis is highest in the first three months of treatment with hormone supplements.

- Hormone supplements are often well suited to female athletes They have less influence on the body’s own production of sex hormones than the “birth control pill” because they release the hormones locally in the uterus.

- In particular, women who participate in strength or speed sports benefit more from their body’s own hormones than from synthetic ones.

You might also be interested in:

Complementary types of training to jogging can help us run more efficiently, faster, and recover better. Read more